The Legacy of William F. Buckley Jr. at UW-Madison

The conservative icon visited Madison on multiple occasions and the movement he built can still be seen on campus

One hundred years after the birth of William F. Buckley Jr., the legacy of the intellectual pioneer of the modern conservative movement endures. A prominent public figure, the founder of National Review, and host of Firing Line, Buckley defined the conservative movement in fractured postwar America. Buckley helped build a coalition that blended libertarian thought, traditionalism, and anti-communism, culminating in the Reagan administration.

Buckley believed that universities mattered because they trained citizens. He thought higher education should be a place where students encounter and engage with beliefs outside their comfort. His 1951 book God and Man at Yale was built on that premise and set the framework for how conservatives would think about universities for decades.

His influence extended to Madison, where his visits sparked controversy and conversations. In 1961, Buckley drew an overflow crowd at the Madison Inn in a speech hosted by conservative students. That speech came shortly after the National Student Association, a confederation of student governments, denied him the podium at their national convention. Buckley criticized the NSA for that decision, and said, “conservatism has grown up because students have grown up, surveyed the world, and disliked what has met their eye.” According to the Wisconsin State Journal, “the session was enlivened by hissing and booing and applause.”

In his speech, Buckley criticized both the John Birch Society and the policies of then-President John F. Kennedy. “The conservatives, facing the crisis of our times, can resist the temptation to use government to realize quick ends at the expense of individual rights and liberties,” Buckley said. “A society dominated by millions of laws, that makes room for millions of bureaucrats, restricts freedom.”

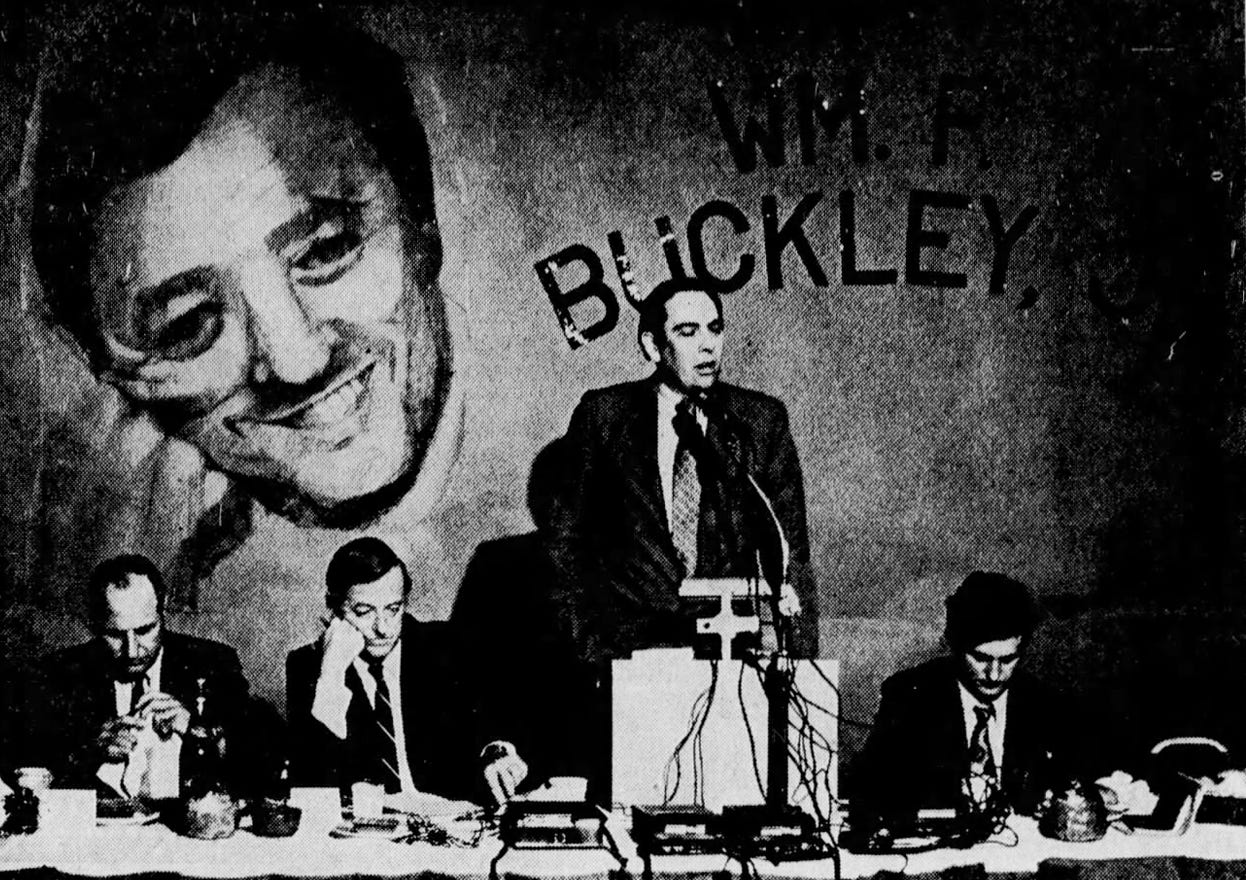

Buckley returned to Madison in 1971 for a Badger Herald fundraiser. At the time, the Herald was a conservative publication similar to The Madison Federalist. Addressing a crowd of 600 supporters, Buckley harshly criticized radicals at UW-Madison. “Reason cannot reach the revolutionary vapors on which the young revolutionaries are stoned,” he said. He praised the Herald’s coverage of campus issues, and said the paper was a sign of “our will to survive” in contrast to the revolutionaries who “are doing their best to destroy freedom.”

Buckley’s final appearance at the University of Wisconsin-Madison was at a Distinguished Lecture Series speech in 1993. He said Bill Clinton was a “mythogenic figure,” but America had shown “the fortitude to survive electoral vicissitudes.” He continued, “Utopia has never come when an omnipotent government is everywhere around us.”

Buckley refused to have his column syndicated in the Capital Times after a dispute with one of its publishers, and when the paper was mentioned, Buckley quipped, “Your paper hasn’t become a ghetto of despair without me, have you?”

Donald Downs, political science professor emeritus, compared the event to “Nixon going to China” in an email to The Madison Federalist. Downs said he “joined the dozen people who had dinner with him at a now-defunct restaurant on State Street” and had the opportunity to speak with Buckley. He was later given the paper on which Buckley had written the speech, saying he was “surprised to see that it was handwritten in small writing all crammed together with red ink revisions scribbled on it.”

During a period when UW-Madison was in the national spotlight during free speech battles of the 1990s and early 2000s, the willingness of students to bring Buckley to campus despite protests reflected a desire for a more intellectually diverse and less confrontational environment. Downs said university would be a “more interesting and challenging place” if similar initiatives took place today.

READ MORE OF DOWNS’S REFLECTION HERE

Buckley played a major role in inspiring the formation of student groups across the country that defend free speech, religious liberty, and constitutional rights, including Young Americans for Freedom.

In 1969, UW-Madison student David Keene became the national chairman of Young Americans for Freedom, where he worked closely with Buckley. Keene is a conservative giant in his own right. He worked for Senator James L. Buckley (William’s brother) and was later chair of the American Conservative Union and the National Rifle Association. Keene’s college roommate was former Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson. The conservative student movement that launched both men’s careers could be traced to Buckley.

Today, UW-Madison’s Young Americans for Freedom chapter prospers, and the badger featured on the latest two print editions of The Madison Federalist has been affectionately named “Buckley Badger.” The Federalist is affiliated with the Fund for American Studies, an organization Buckley co-founded.

In addition to UW-Madison, Buckley visited the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh in 1962, sponsored by the Conservative Club. He also delivered the convocation speech at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point in 1978. In 1979, Buckley gave a speech sponsored by the Associated Students of Marquette University.

Three episodes of Firing Line were filmed at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee in 1974, where Buckley interviewed Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt, Senator Eugene McCarthy, and Representative (later Secretary of Defense) Les Aspin. UW-Madison student John Felder also appeared on Firing Line to discuss the Black Student Strike of 1969.

Above all, Buckley insisted on intellectual seriousness and principled boundaries. Buckley’s centennial offers not only a reflection on the past but a challenge for the present. For a university that prides itself on “sifting and winnowing,” and on the Wisconsin Idea of extending education and dialogue, Buckley’s legacy serves as a reminder that intellectual diversity is not a burden but a necessary condition of campus life. For a conservative movement struggling to find its identity, Buckley serves as a reminder to not be driven by hatred.